“My analogy is like coming across an accident,” she says. All his music was missing.”Īs a consequence, Leach became “an accidental musicologist”, hunting for Eastman’s lost works.

#Julius eastman series#

Attempting to track down an Eastman piece for 10 cellos she’d seen him conduct in 1981, Leach encountered a series of dead ends: “It gradually dawned on me. In 1998, Leach began teaching composition at Cal Arts. We all thought we were pretty hip back then, but Julius walked in off the street, dressed in leather and chains, drinking from a glass of scotch at 10 in the morning. “I’d first met him in New York, spring 1981. “That’s the first I knew he’d died,” says composer Mary Jane Leach. Following his death, eight months passed before the first obituary. He lived rough for a few years in Tompkins Square Park, then drifted off the map. Effectively homeless, still composing, Eastman became increasingly reliant on alcohol and drugs. All his belongings, including his music, were abandoned on the street and, when he didn’t return, taken to the city dump. The lessons petered out things became difficult for Julius.”Īround the end of 1981, Eastman was evicted from his East Village apartment due to unpaid rent.

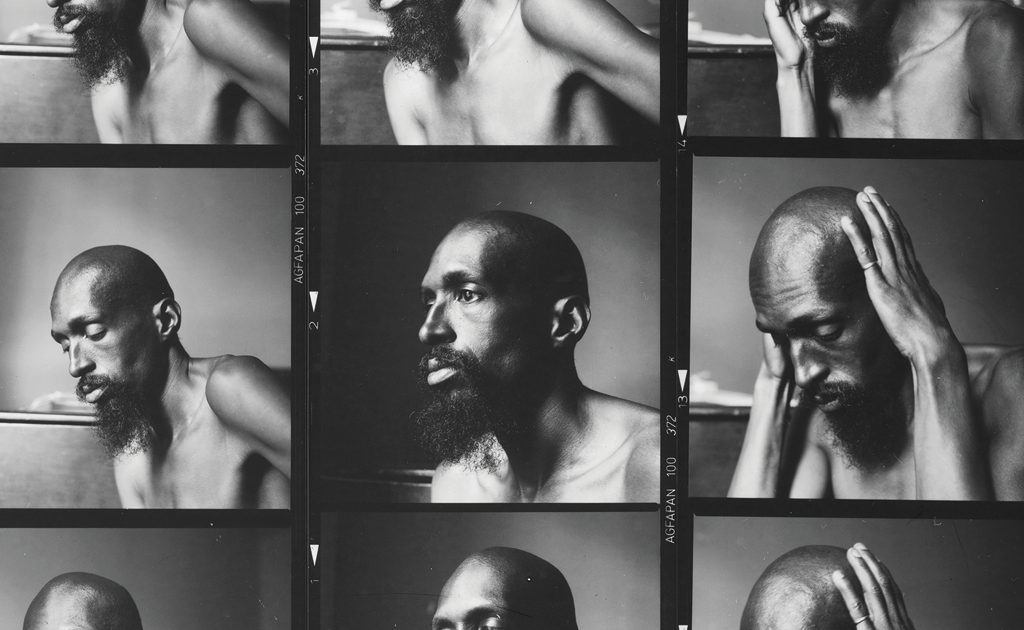

I still have my copy of Gymnopédies, smeared in red. He was saying, I have all of this knowledge I want to pass on. I now wonder if that was a test, to see if it would push me away. My first lesson was to play Satie, whilst he put on lipstick. He said, ‘Don’t you play with the Lounge Lizards? I want to meet their keyboard player.’ He wanted to give me composition lessons. “I first met Julius at the Bar on Second Avenue. “That Lower East Side gay scene was just emerging,” says Evan Lurie, keyboardist and co-founder of downtown no-wave jazzers the Lounge Lizards. It’s his operatic vocals you hear on Dinosaur L’s 24>24 Music. He conducted the orchestras for Russell’s Instrumentals and Tower of Meaning. Instead, Eastman immersed himself in Manhattan’s downtown scene, collaborating with Meredith Monk, Robert Wilson and, significantly, Arthur Russell. Do you know how many doors that would have opened?” He moved to New York in 1976, just as Pierre Boulez wanted to do Mad King with him. Julius started identifying with the black community. “Cage thought it was a parody of him,” says SEM co-founder Petr Kotik. But he regretted it because Cage was so angry. “He said, I hate that Cage never speaks about sex. “Julius tried to ‘out’ Cage,” Di Pietro says. In a pivotal SEM performance of John Cage’s Song Books in June 1975, with Cage present, Eastman staged a lecture on “a new system of love” in which he undressed a male volunteer (possibly his boyfriend), while making sexual overtures in acrobatic baritone. Yet, as an out gay black man working in a predominantly straight white environment, Eastman grew progressively more uncomfortable. Through bravura piano and vocal recitals at Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center, his reputation grew, culminating with a Grammy-nominated performance as George III on the 1973 recording of Peter Maxwell Davies’s Eight Songs For A Mad King. A former child soprano and ballet dancer from Ithaca, New York, who studied piano and composition at Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute, Eastman first came to prominence with Buffalo University’s early 70s avant-garde SEM Ensemble, performing with Morton Feldman, John Cage and Pauline Oliveros. When Eastman died of heart failure, alone, in Millard Fillmore hospital in Buffalo, New York, on, aged just 49, his work disappeared with him. And all these years I’ve been telling people I don’t have any.” And I found all these letters from Julius, and a handwritten score. “I came down this morning,” says Pietro, an audible catch in his voice.

We should be discussing the release of Femenine, a recently discovered 1974 recording by his old friend, the late composer Julius Eastman, but memories keep getting in the way. It’s an August afternoon in Columbus, Ohio, and 66-year-old teacher and composer Di Pietro is in his basement looking through old letters. He pulled out this Brahms lieder, sat at my piano, and played. He was wearing this oversize jacket with all these pockets.

I gave him what I could, offered to make him an omelette, buy him cigarettes and drive him to the station. “He was homeless and looking for bus money to get to California. “Julius showed up at my door,” remembers Di Pietro. T he last time Rocco Di Pietro saw Julius Eastman was on a freezing April morning in Buffalo in 1989.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)